What’s New at Wildlands

Human History of Wildlands: Striar Conservancy

Striar Conservancy in Halifax. Photo by Jerry Monkman.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Wildlands Trust’s land conservation work is all about context. No parcel is protected before the staff scrutinizes its place within regional trends in ecology and land use. Last month, I decided it was time for “Human History of Wildlands” to adopt the same approach. In accordance with Wildlands’ decades-long initiative to protect land along the Taunton River, I zoomed out my lens from individual preserves to the entire Taunton River watershed. From this 30,000-foot view, much came into focus about how the region has evolved over time and why it’s so critical to protect. For the next few months, I will zoom back in to the diverse histories of Wildlands preserves within the Taunton River watershed. But first, I encourage you to read "Human History of Wildlands: The Taunton River Watershed." It is from this context that the following accounts will come to life.

Striar Conservancy is a 162-acre Wildlands showcase preserve located in Halifax, on the northern bank of the Winnetuxet River. It was acquired by Wildlands in 1999 from the Striar family, with hiking trails established the following year. The Town of Halifax's Randall-Hilliard Preserve abuts Striar from the south, creating a cushion of undeveloped land on both sides of the Winnetuxet.

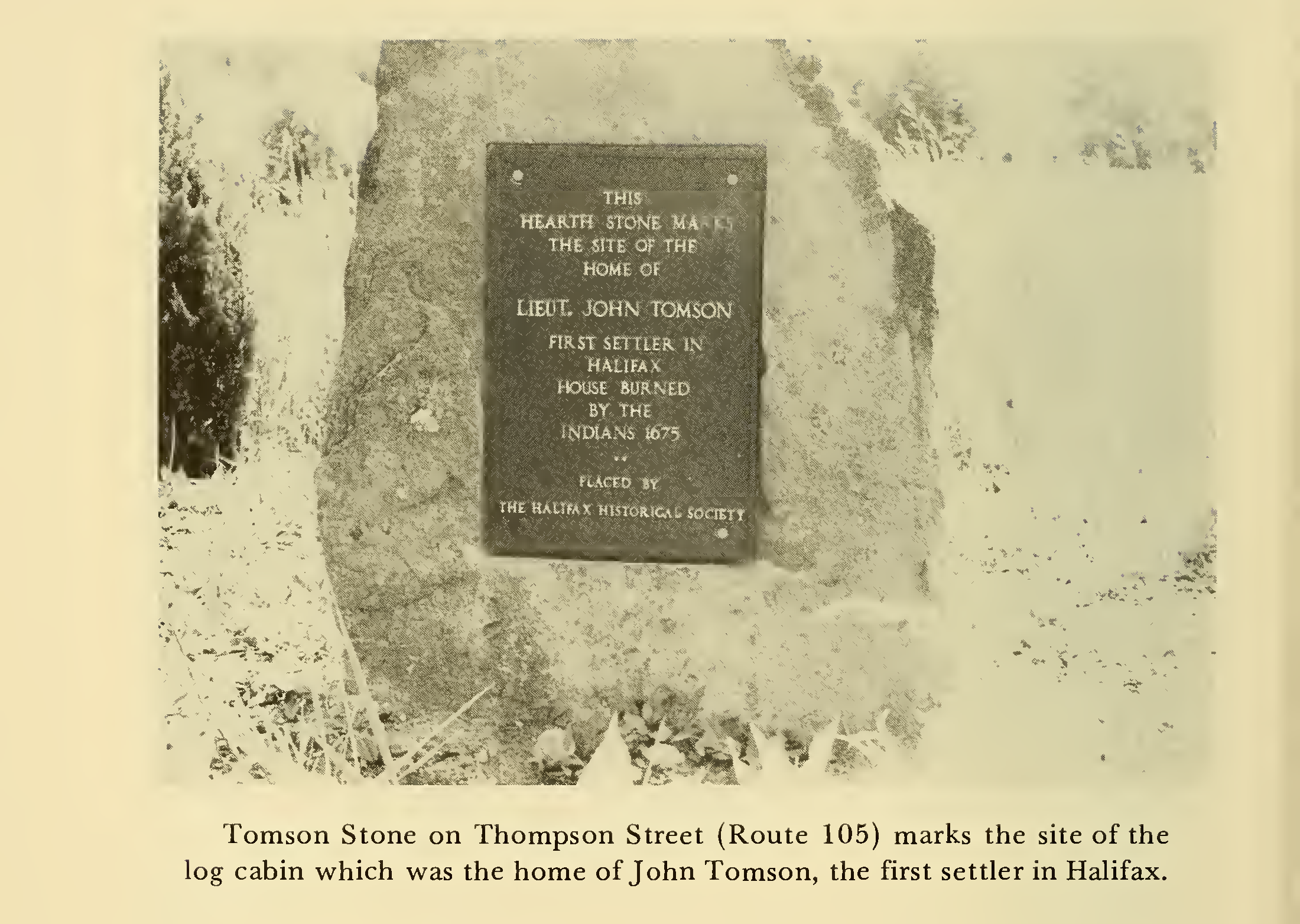

The area that would become Halifax was part of the 1661 "Twenty-six Men's Purchase" by settlers from the Plymouth Colony. The land contained parts of several current towns, including Middleborough, Plympton, Pembroke, and Halifax. In 1669, one of these 26 men, John Tomson, built his house on a large landholding of 6,000 acres on the Winnetuxet River. What would become Thompson Street (named after John, albeit with an alternate spelling) was described as an ox trail and cart path between Middleborough Green and the Tomson homestead. Other settlers soon followed. The land was fairly flat, swampy, and muddy, with few rocks owing to its past as a lakebed for Glacial Lake Taunton. It did have abundant woodlands of pine, oak, and especially the highly valued cedar, clearing the way for logging to become a principal industry.

From History of Halifax, Massachusetts by Guy S. Baker (1976), page 126.

The initial settlers didn't prosper for long, because in 1675, King Philip's War broke out. Since their houses were spread out along Thompson Street, they could not be easily defended, and the raids burned many. John Tomson and others abandoned their homes and fled to a fort in Nemasket. Tomson took charge, but it soon became apparent that that their location was untenable, so he led the settlers to Plymouth for safety. Tomson soon became known as Halifax's "First Soldier."

The next year, Captain Benjamin Church fought and captured 120 of the Monponsett ("near the deep pond") band of the Wampanoag Tribe at White Island, imprisoning them until the end of the war in Plymouth. Monponsett was the original name for the town of Halifax, and Monponsett Pond lies near the town’s center.

When the war was over, settlers returned and rebuilt their homes, and the community grew once again. Forestry and now farming were taken up by the residents. The Winnetuxet River’s flow proved suitable for waterpower, and dams were soon built by the Thompsons, the Sturtevant family, and others. The dams powered sawmills, granaries, and a thriving charcoal industry. Remains of the Thompson Mill dam remain to this day at Striar Conservancy.

From History of Halifax, Massachusetts by Guy S. Baker (1976), page 168.

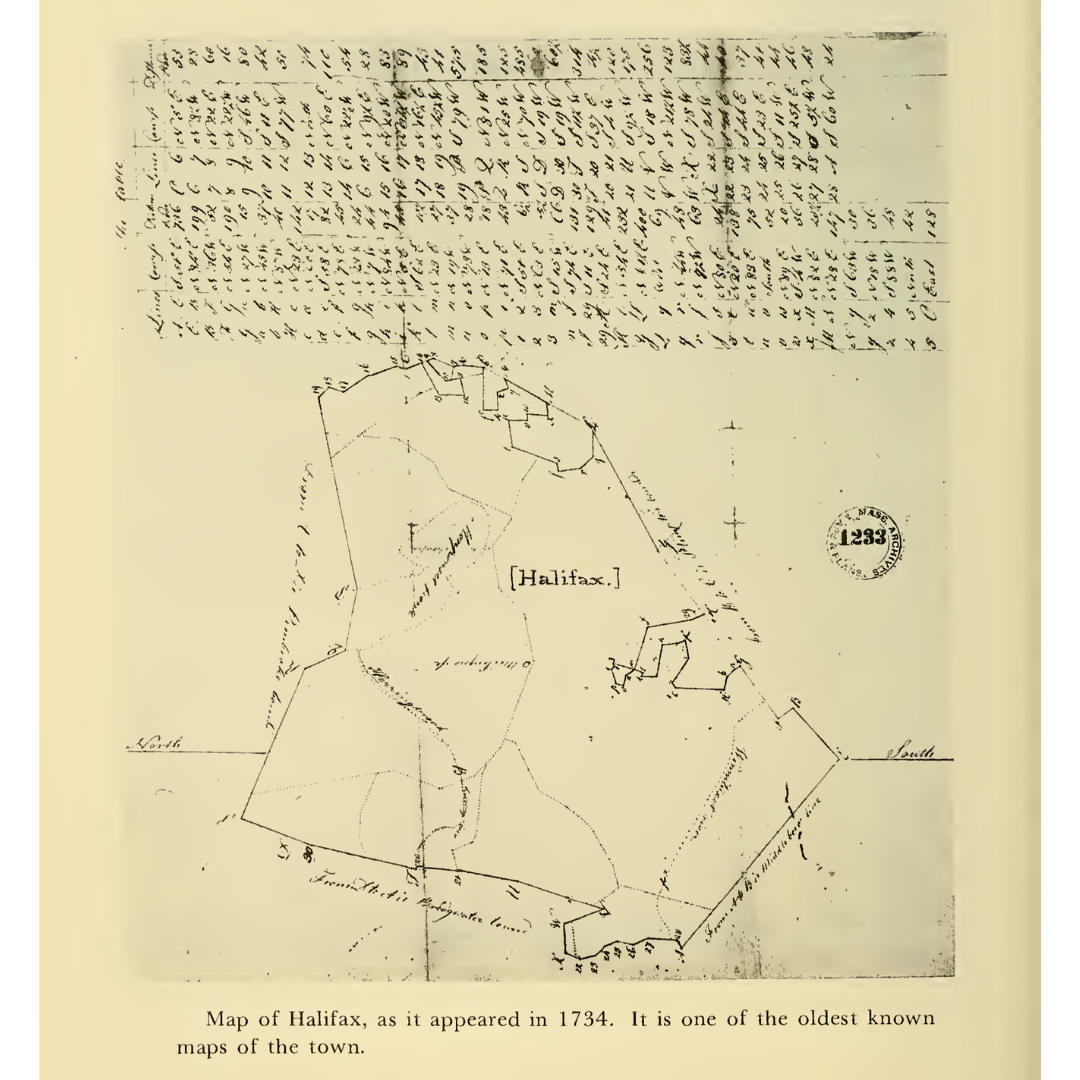

In 1677, the first public grammar school was formed, although for most of the next 100 years, there was no school building; instead, classes were held in private homes. In 1734, the Town of Halifax was incorporated from parts of Middleborough, Plympton, and Pembroke. Agriculture grew in importance, with cranberry cultivation leading the charge, as in the rest of Southeastern Massachusetts.

Halifax played an active role in the American Revolution, hosting the longest continuous militia company in Massachusetts. In fact, the first official mention of the war was made in Halifax, before it even began: "On December 26, 1774, it was voted that minutemen drawn out for military exercise shall have their pay for two half days in a week at 8 cents per half day." A week later, the town voted to send a member, Ebenezer Thompson, to the Provincial Congress in Cambridge.

From History of Halifax, Massachusetts by Guy S. Baker (1976), page 115.

Halifax experienced slow, steady growth in the 19th and 20th centuries. Forests returned to the landscape in the place of abandoned farms. Maintaining its rural character and continuing cranberry production, Halifax evolved into an attractive modern bedroom community.

Here, I have to include what some might see as a digression, but many might find entertaining. During World War II, a Halifax native made national headlines as the person who invented graffiti. His name was James Kilroy. In the 1940s, he worked at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy. Perhaps out of boredom, he began signing his name on ships being built. The idea was picked up by servicemen, and soon the phrase "KILROY WAS HERE," often accompanied by a man with a big nose looking over a fence, adorned military ships, buildings, and equipment. Few might remember it now, but WWII vets and baby boomers might remember Kilroy as a local celebrity.

Kilroy engraved on the National World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C.

When you visit Striar Conservancy, the preserve’s natural history will speak louder than its human history. With pristine frontage on the Winnetuxet River, five certified vernal pools, and various other woodland and wetland habitats, Striar is home to as much wildlife as any Wildlands property. But when you imagine the battles fought, products made, and communities sustained in the area, the human stories are equally audible—if you’re willing to listen.

Gray treefrog at Striar Conservancy in Halifax. Photo by Rob MacDonald.

Resources utilized in the preparation of this history include:

The History of Halifax, Massachusetts by Guy S. Baker, 1976.

Yesterday and Today: 250th Anniversary of Halifax, 1734 -1984.

“History of Halifax Massachusetts,” Mega Matt’s Ponderings, YouTube.

Recollecting Nemasket, Michael Maddigan, 7/17/2009.

The Human History of the Taunton River Watershed, April 2025, Wildlands Trust.

Photographs and background by Rob MacDonald: robsphotos.blog/wildlands-trust/striar-conservancy/index.html.

Thank you to Wildlands Trust Communications Coordinator Thomas Patti for his editing and encouragement.

Human History of Wildlands: The Taunton River Watershed

Striar Snake River Preserve in Taunton. A project is underway to improve public access at this preserve.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Those of you who have been following our "Human History of Wildlands" series know that the approach so far has been to tackle one preserve or one community at a time and to dig as deeply into that story as historical resources allow. However, when I started researching the history of Wildlands Trust’s Great River Preserve in Bridgewater, it occurred to me that there was a different kind of story here, not just of one preserve, but of an entire region—namely, the Taunton River watershed. Here, I take a broader look at this 500-square-mile area, one within which Wildlands Trust and its partners protect a variety of landscapes that are important as individual parcels but carry even greater significance in the context of their shared history. In upcoming entries to this series, we will zoom back in to the stories of individual preserves in the watershed, like Great River Preserve, Striar Conservancy in Halifax, and Wyman North Fork Conservation Area in Bridgewater. Today, we will take this broader view.

A watershed is a land area within which all rainfall and snowmelt funnels into the same place. A raindrop in Foxborough, even if it’s 15 miles from the headwaters of the Taunton River, will eventually work its way down smaller streams or in groundwater to the Taunton and empty into Mount Hope Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. So, the point where that raindrop first splashed down in Foxborough is part of the Taunton River watershed.

The map below will help convey the size of the Taunton River watershed and its importance to Wildlands’ work. Of the 57 cities and towns that Wildlands Trust serves, 30 lie at least partially within the Taunton River watershed, which encompasses 562 square miles across Southeastern Massachusetts. Wildlands protects over 2,150 acres of land in the Taunton River watershed through outright ownership, Conservation Restrictions, and deed restrictions.

The Taunton River watershed is home to geographical and historical features that exist nowhere else in Massachusetts. It features the longest undammed coastal waterway in the state. This is in part because it drops only 20 feet from its source in Bridgewater to its mouth in Fall River, curbing its power generation potential. The Taunton River is tidal up to the City of Taunton, meaning it contains salt and brackish water for about half of its length.

The watershed is home to over 500,000 people across 43 towns and cities, covering portions of three counties. Despite the dense settlement around it, the Taunton River is a federally designated Wild and Scenic River. The region is also home to the largest freshwater swamp in southern New England, the nearly 17,000-acre Hockomock Swamp.

These features and many others play important roles in the area's human history. Now, let’s move back in time.

Pre-history

As the glaciers receded between 12,000 and 13,000 years ago, they left a landscape scraped and scoured, with piles of rocks, rubble, moraines, eskers, and other geological features. Across central Southeastern Massachusetts, a large moraine created a debris dam that prevented melting glacial water from draining into the ocean. The result was Glacial Lake Taunton, which spanned 54 square miles and plunged 130 feet deep. The lake lasted for about 300 years before the dam broke.

Glacial Lake Taunton. From “Understanding Geological History when Selecting Trenchless Installation Methods” by Haley & Aldrich.

When the dam finally breached, the rushing water spread a mix of gravel and mud across the watershed area, building the foundation for some of the richest forests and farming soils in Southeastern Massachusetts. It also created today's Taunton River and its many tributaries.

People soon arrived. We know a good deal more about the pre-European history of the Taunton River watershed than of much of the rest of Southeastern Massachusetts. In fact, some of the oldest archeological evidence of human habitation in New England comes from digs, finds, and studies in Bridgewater, Middleborough, and the "Titicut" site, dating back more than 9,000 years. The watershed was heavily populated for the time. Several area names survive. Cohannet, Tetequet, Titiquet were all used by the resident Wampanoag Tribe to describe the river and its valley.

The flat, slow-flowing river also became a major route for Native Americans to trade and move seasonally to productive hunting and fishing areas. The 72-mile Wampanoag Canoe Passage was a well-traveled route that allowed relatively easy passage between Cape Cod Bay and Narragansett Bay via the North River and the Taunton River. The passage has been restored and cleared in some areas and can be followed today.

Along the route, Natives likely passed through the Hockomock Swamp, derived from "Hobomock," the deity tied to death and disease, but also to the spirits of ancestors. It was also an area favored as a sanctuary and for its rich game and hunting resources.

Great River Preserve in Taunton.

European Settlement

After 1620, the English settlers of the Plymouth Colony soon moved west and found that the Taunton River area held great promise. Good soil. Easy river travel. And while the main river's current was too slow to produce power for mills, tributaries such as the Town, Matfield, Winnetuxet, Nemasket, and Three Mile Rivers all tumbled into the valley with sufficient energy to provide waterpower and to support the largest spring runs of alewives and river herring in the state.

The watershed was initially part of the "Duxbury Purchase," but settlement soon created towns such as Taunton in 1637 and Bridgewater in 1645, and ultimately Plymouth and Bristol Counties. Farms thrived upriver, while ironworks and shipbuilding made Taunton a growing city. Eventually, Taunton earned the name "the Silver City" due to its reputation for silversmithing and jewelry making.

As with nearly all of Southeastern Massachusetts, and much of New England, this prosperity was not to continue without setbacks. The most notorious one was King Phillip's War from 1675 to 1676. Initially good relations between European colonists and the Wampanoag Tribe and its chief Massasoit, crucial to the Plymouth Colony's early survival, had in two generations deteriorated into war. The Tribe, led by Massasoit's son Metacomet (who chose the name King Philip), was feeling taken advantage of by the colonists. A revolt ensued, and the Taunton River area, especially Hockomock Swamp, was its epicenter. While the hostilities eventually reached all of New England and upstate New York, the Plymouth Colony and adjacent Rhode Island bore the brunt of the fighting. Whereas the colonists feared and avoided the swamp, the Natives found safety and sanctuary there. In fact, the war only ended when the colonists finally entered the swamp and routed Metacomet and his people. In the end, King Phillip's War was the costliest in terms of property destruction and death—to both colonists and Natives—in all of colonial America.

The Taunton River passes through the forests of Wyman North Fork Conservation Area in Bridgewater. In 2024, Wildlands acquired an additional 90 acres directly across the river from Wyman North Fork, further protecting this section of the Taunton River corridor less than two miles from its headwaters.

After the war, colonial prosperity resumed, and towns grew and flourished. Many attempts to drain Hockomock Swamp ensued, but each ultimately failed. The swamp served as a natural "sponge," absorbing water and preventing the kinds of floods that periodically disrupted life on many nearby rivers. Indeed, failures to drain the swamp substantially contributed to the Taunton River’s wild and pristine state today. Similarly, the Taunton’s incapacity for waterpower has benefited the watershed’s ecological health, as it kept the river undammed, free-running, and surrounded by forest and farmland. Thanks to its unique natural characteristics that stifled colonial industrialism, the Taunton River is now a federally designated National Wild and Scenic River.

Today, the Taunton River watershed is home to many wonderful nature preserves. Wildlands Trust, MassWildlife, the Taunton River Watershed Alliance, and its cities and towns work together to protect this special place. Great River Preserve, Wyman North Fork Conservation Area, Striar Conservancy, Brockton Audubon Preserve, and soon Striar Snake River Preserve in Taunton are some of the Wildlands properties where you can see the results for yourself.

To learn more, please see our website at wildlandstrust.org and visit some of our preserves in the Taunton River watershed.

Striar Conservancy in Halifax is located on the bank of the Winnetuxet River, a tributary of the Taunton River.

Learn More

Resources for this article include:

The Taunton River Watershed Alliance: savethetaunton.org

Tetiquet To The Sea: A History of the Taunton River: oldcolonyhistorymuseum.org/product/tetiquet-to-the-sea

Wild and Scenic Taunton River: srpedd.org/environment/wild-and-scenic-taunton-river

Archaeology of Dighton: plymoutharch.tripod.com/id157.html

Understanding Geological History When Selecting Trenchless Installation Methods: haleyaldrich.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/NETA

The Wampanoag Canoe Passage: North and South River Watershed Association, "River Watch," April 2015.

Thanks to Thomas Patti for his editing and encouragement, to Owen Grey for his mapping assistance, and to Tess Goldmann for her analysis of Wildlands’ holdings in the Taunton River watershed.

If you have photographs, historical documents, or maps related to the history of the Taunton River watershed, we want to see them! Please send any information to communications@wildlandstrust.org.

Hunting Season Safety

Updated: October 2024

Hunting season is back upon us this fall in Massachusetts! Wildlands Trust has four properties that permit hunting during this time:

Barnes Rymut Preserve, Halifax

Hunting is prohibited on all other Wildlands Trust properties.

Still, boundaries can be confusing and hunters sometimes cross into prohibited areas unknowingly. Please be mindful when you are out in the woods this year, wherever it is that you like to hike, run, or ride. The best way to protect yourself is to wear blaze orange like our staff does!

While hunters are required to wear blaze orange during certain seasons, Mass Wildlife recommends that all outdoor users who are in the woods during hunting season wear blaze orange clothing as a precaution, and that pets wear an orange vest or bandana for visibility.

You can learn more at mass.gov/topics/hunting.

Have a great fall, and stay safe!

Volunteer Spotlight: Rob MacDonald

When and how did you first learn about Wildlands Trust?

I believe I first learned about Wildlands Trust through the Willow Brook Preserve in Pembroke. It’s pretty close to my house and one day, while driving down Route 14, I spotted the entrance. Eventually I stopped by and explored it with a walk through the property.

How did you discover the Adopt-A-Preserve (AAP) program?

We [Rob and his wife] had been members of Wildlands Trust before the AAP program existed and had been involved with volunteer work at Wildlands through some of your workdays. Eventually I heard about the AAP program from someone I knew who was working at [Wildlands]. They informed me that Erik [Boyer] was looking for volunteer help with the AAP program.

Rob MacDonald (far right) poses with other volunteers at Brockton Nature Festival.

How many years have you been a part of AAP?

Well, I was first involved with Wildlands Trust in about 1999 when I participated in a corporate workday at Willow Brook Preserve. This was an organized community service event with Bank Boston employees where we burned brush and removed invasive species to clear out the meadow habitat near the beginning of the trail system. Once AAP was created in 2014 and I heard about it, I joined shortly thereafter.

What Wildlands properties have you “adopted”?

Striar Conservancy in Halifax and Tucker Preserve/the Indian Head River loop, which goes through Pembroke, Hanson, Hanover, Plymouth County land, and private property.

What is your favorite thing to do while out on monitoring visits?

Photography. I am always looking for shots of birds while on my monitoring visits. And then, during the spring when vernal pools are active, I like to look for amphibians to photograph. Typically, I bring out a long-lens camera for pictures of birds and a macro-lens for taking close-up pictures of fungi and amphibians.

What are some highlights for you along the Indian Head River Trail (IHRT) loop?

The bluff in Tucker preserve where the trail cuts through a hemlock grove opposite of the tack factory along the river is a nice section of trail. I also really like the babbling stream you encounter towards the back side of Tucker. It’s one of several spots that remind me of New Hampshire. I also really like the section of trail that cuts through Rocky Run, which is beautiful town of Hanson conservation land.

What have been your favorite wildlife sightings at Striar and Tucker?

River otter, which I’ve encountered at both Tucker and Striar. I recently saw one at Tucker, along the Indian Head River, soon upon entering Tucker from Pembroke Conservation land. The otter was resting on the ice on the river, eating a fish that it had caught.

When I saw an otter at Striar, I was looking out at a bend in the Winnetuxet River. I heard a bark and the otter slipped into the river behind me. I suspect it was voicing a warning signal to another otter somewhere in front of me. In terms of exciting bird sightings, I‘ve seen a wide variety of birds including barred owls, yellow cuckoos, ovenbirds, wood ducks and a palm warbler at Striar.

What is the most memorable experience you have had while at a Wildlands property?

At Striar, I have done vernal pool walks where participants come out at night to explore what they can find in the pools. Kids and adults alike get extremely excited about the chance to dip their hands into the pools to see what they find. Many people would not normally go on hikes at night on their own so the opportunity is unique and exciting for that reason too.

What is your favorite thing about AAP?

The monitoring visits present you with an opportunity to pay greater attention to the place you are in. I definitely focus more on the details of the surroundings than I would on a hike. My responsibilities as an AAP member makes me much more attentive while out on a preserve. }

What is it like being a part of the volunteer hike leader program?

On several occasions, people have come to one of these Wildlands Trust hikes and mention that they were sometimes hesitant to go out and hike in the woods alone. These organized group hikes gave them the opportunity to get out in a group atmosphere and enjoy exploring the varied Wildlands Trust preserves. So being part of a program that affords these folks, who might no otherwise get out into the woods, is pretty nice.

Are there any nature preserves in the region that you like to visit outside of the ones you adopt?

Burrage Pond Wildlife Management Area, a 1,638 acre MassWildlife-managed preserve that stretches through Hanson and Halifax is my favorite. The preserve is a habitat for beavers, otters, and many different species of birds. Burrage Pond’s landscape includes dormant cranberry bogs. Some of these ex-cranberry bog areas have remained open to develop into grassland habitats and others have been flooded to allow for habitat for aquatic birds. The management area also includes an interesting floodplain habitat along Stump Brook River that supports Atlantic white cedar and eastern hemlock trees.

I know you have visited for these trails for many years. Have you seen the area change over the years?

I’ve been walking the trails along the Indian Head River for at least 25 years. As for changes, the Hanover section of trail has become more formalized is now a well-marked trail. Also, on the western section of the trail loop, where you cross the bridge on State Street in Hanson, the trail used to be difficult to find because it was completely unmarked. That entrance has now been opened up and is much easier to find. Overall, the trail system has become more formalized and clearer while maintaining the same peaceful and wild feeling I got hiking these trails 25 years ago.

As a resident of Hanson, how do you think the community can benefit from a natural resource like the Indian Head River Trail?

The Indian Head River trail system presents Hanson community members with a beautiful hike along the Indian Head River through Rocky Run Conservation Area, a showcase example of protected, natural, town of Hanson conservation land.

Enhancing the Region Through Conservation

As a regional land trust, Wildlands Trust’s work throughout the South Shore benefits the fabric of our communities in many different ways.

By Membership and Communications Manager Roxey Lay

It’s a new year and with it comes a new year of projects, land acquisitions, public programming and more, all in the name of conservation. Since 1973, Wildlands Trust has committed to conserving and permanently protecting native habitats, farmland and lands of high ecological and scenic value that serve to keep our communities healthy and our residents connected to the natural world. And every year, you and many other supporters like you, make this work possible by renewing your commitment to Wildlands. But why do we do this work? Why are land trusts important?

The state of Massachusetts lists on its website five reasons why land conservation is “critical in preserving and enhancing the quality of life in Massachusetts.” [1] Read on to see how Wildlands’ work directly benefits our region and the residents who call it home.

Protection of water resources

Clean water is essential to any community. Nearly every property within Wildlands’ portfolio contains some type of water resource and a key factor in conserving these ecologically significant properties is that doing so protects against contamination. When water flows over the ground, it can potentially pick up a number of pollutants, “which may have sinister effects on the ecology of the watershed and, ultimately, on the reservoir, bay, or ocean where it ends up.” [2] Those pollutants can also soak into the ground and contaminate groundwater, “where it will eventually seep into the nearest stream…or into underground reservoirs.” [2] By conserving properties that contain and/or abut hydrological resources, Wildlands is able to limit the potential for pollution of those resources and habitat.

Wetlands at Striar Conservancy, Halifax.

Striar Conservancy in Halifax runs along the Winnetuxet River (identified by the National Park Service as one of the top four priorities for conservation along the Upper Taunton River) and combined with the town of Halifax property on the other side of the river, preserves 250 acres along the Winnetuxet. Striar is also host to vast wetland habitat, which, in addition to providing habitat to a number of local species, filters water running along the ground before it enters the river. “Wetlands are filters for water coming off the land, reducing sediment and chemicals in run off before it gets into open water. These chemicals and sediment could kill fish and amphibian eggs, smother bottom feeding wildlife and plants, and clog waterways.” [3]

If water resource protection is something you feel strongly about, you aren’t alone; clean water is a concern for the majority of Americans. In the 2019 Gallup Environment poll, 53% of respondents worry “a great deal” about the pollution of rivers, lakes, and reservoirs and 56% worry “a great deal” about pollution of drinking water. By supporting Wildlands Trust, you are helping keep critical water resources clean.

Providing open spaces and parks for our urban communities

Wildlands’ service region covers 45 towns throughout Southeastern Massachusetts. In Brockton, Wildlands staff have taken on a number of projects since first acquiring Brockton Audubon Preserve in 2012, ranging from land stewardship, tree planting, and youth education. In 2019, Wildlands worked with the city to restore and manage Stone Farm Conservation Area. Together, these two properties provide residents with 230 acres of open space for outdoor recreation, as well as health and environmental benefits that come with having access to public open space:

Hikers head out on a guided hike at Stone Farm Conservation Area during its grand opening at Brockton Nature Festival. (October 2019)

A sanctuary for escaping high summer temperatures and finding shade under a protective canopy.

Access to an open, living laboratory that provides opportunities for environmental education.

Maintaining habitat species biodiversity in Brockton.

Trees trap and store carbon from the atmosphere, as well as keep the city cooler.

In addition to our growing presence in the city, Wildlands’ community outreach manager, Conor Michaud, has recently been asked to serve on the city’s open space planning committee. Wildlands looks forward to continuing outreach efforts within the city and connecting residents to the land.

Creating and enhancing outdoor recreation opportunities statewide

Wildlands Trust’s monthly programming and events provide residents and visitors throughout Southeastern Massachusetts opportunities to experience the open space we protect. Offering a variety of options, participants can go on a general or themed hike, take a yoga or guided meditation class, get creative with arts and crafts projects, attend an educational presentation, and more.

Attendees watch intently during “Eyes On Owls”, a live owl presentation at Davis-Douglas Farm.

Wildlands’ public preserves are also host to trail systems that are inclusive to visitors of varying abilities. Trails can range from gentle field walks like at Cushman Preserve in Duxbury, to more challenging and hilly terrain like at Halfway Pond Conservation Area. In Bridgewater, the 125 acres comprising Great River Preserve (a vital link in a 1,400-acre stretch of river corridor) contains a handicap-accessible entrance and a wheelchair-accessible path leading from the property’s fields to the Taunton River.

With programs tailored to appeal to a number of interests and preserves with a wide-range of trail systems, Wildlands works to connect everyone to the natural world.

Interested in joining in on the fun? Find upcoming Wildlands programs and events at wildlandstrust.org/events or check out a trail map at wildlandstrust.org/trails

Preserving working farms

Wildlands’ portfolio contains a number of properties with Agricultural Preservation Restrictions (APR). This restriction protects the property from non-agricultural development and ensures it remains in a state of active agriculture. School House Field at Eel River Preserve is an example of how Wildlands partners with local farmers to help them find land while also maintaining the active agricultural status of a property. The most recent partnership on this land is with local brewery owner Paul Nixon, who has been growing hops on the property since 2018.

Cows graze in the fields at Anderson Farm, West Bridgewater.

Wildlands also works with state and town governments on APR projects. In 2004/2005, Wildlands brokered the deal to preserve the 145-acre Historic O’neil Farm in Duxbury. The restriction placed on this property, which has “been in continuous agricultural use since the early 1700’s” [4] and remains as the last working dairy farm in Duxbury, ensures it will continue to operate as a farm in perpetuity. In 2010, Wildlands also helped save the 116-acre Anderson Dairy Farm in West Bridgwater by working with the Massachusetts Department of Agriculture, town of Bridgewater, and the Anderson family to place an APR on the property. The farm’s importance lies not only in its significance to the town’s farming heritage, but also in its location. The property sits along the Town River (a tributary to the Taunton River) and Hokomock Swam (the largest freshwater wetland in Massachusetts), which provides habitat for various wildlife. Most recently, Wildlands is again working with the town of Duxbury, this time to save the 17-acre Herrington Farm.

The connection between Wildlands and local farms extends into its youth programming as well. During the summer, Wildlands’ Green Team members visit local farms like Bay End Farm in Bourne to learn about organic vegetable farming. Team members take part in the entire farming process, helping out with planting, weeding, harvesting and processing various crops. At Soule Homestead Education Center in Middleborough, team members assist in invasive species removal in pastures and learn about animal husbandry.

Protecting wildlife habitat

Prior to Wildlands acquiring a property, there are a number of criteria it must meet, such as outstanding or noteworthy ecological significance. Lands that fit this criterion contain rare or unusual habitat types, provide habitat for rare or endangered species, contribute to local and regional habitat diversity, and/or possess a BioMap Core Habitat or Supporting Natural Landscape designation.

Rich with diverse river habitat, including marshes and seepage swamps, along the Winnetuxet River, Striar Conservancy supports a variety of local species like the uncommon river otter, wood duck, woodcock, and ruffled grouse. The 168 acres of undeveloped land comprising the preserve also provides habitat for deer, fox, over 90 species of birds like the upland sandpiper and barred owl, as well as state-listed rare species, like the bridle shiner, Coopers hawk, and Mystic Valley amphipod.

Halfway Pond peaks through pine trees at Halfway Pond Conservation Area, Plymouth.

Halfway Pond, at Halfway Pond Conservation Area, provides habitat for the federally endangered northern redbelly cooter (formerly known as the Plymouth redbelly turtle), and also supports six mussel species, including two state-listed rare species. Southeastern Massachusetts is also host to the Massachusetts Coastal Pine Barrens, a unique ecoregion which can be found on Wildlands’ Plymouth properties. This specific habitat is critical to the survival of a number of species. In fact, “the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Wildlife has state-listed 182 species of plants and animals in the Pine Barrens ecoregion as endangered, threatened or a species of concern.” [5]

Climate Change

With nearly 10,000 acres of land in Wildlands’ portfolio, it has become increasingly important for Wildlands to consider the resiliency of these lands and the region overall. In 2019, Wildlands added a criterion into the organization’s mission statement which focuses on climate mitigation and the adaptation potential of a property acquisition. The intention of this benchmark is to help the organization identify lands that contain habitats which are expected to be affected by climate change more so than others (cold-water streams, tidal marshes, and vernal pools).

Wildlands has also incorporated this outlook into its current holdings. While creating this new criterion, Wildlands analyzed the properties currently in its portfolio, created a vulnerability assessment for each one, and a hybrid management strategy. Through the direct protection of critical climate-resilient habitats, adjacent land parcels, and modifying current management practices, Wildlands hopes to increase the region’s overall resiliency to climate change.

Supporting land trusts like Wildlands Trust is not just about protecting land, it’s about enhancing the quality of life within your community. The benefits that come from land protection and the organizations that serve that purpose, extend out into multiple aspects of our region and set an example for other parts of the state, country and world. We thank you for your dedicated support and look forward to continuing to enhance the beauty and health of Southeastern Massachusetts for years to come.