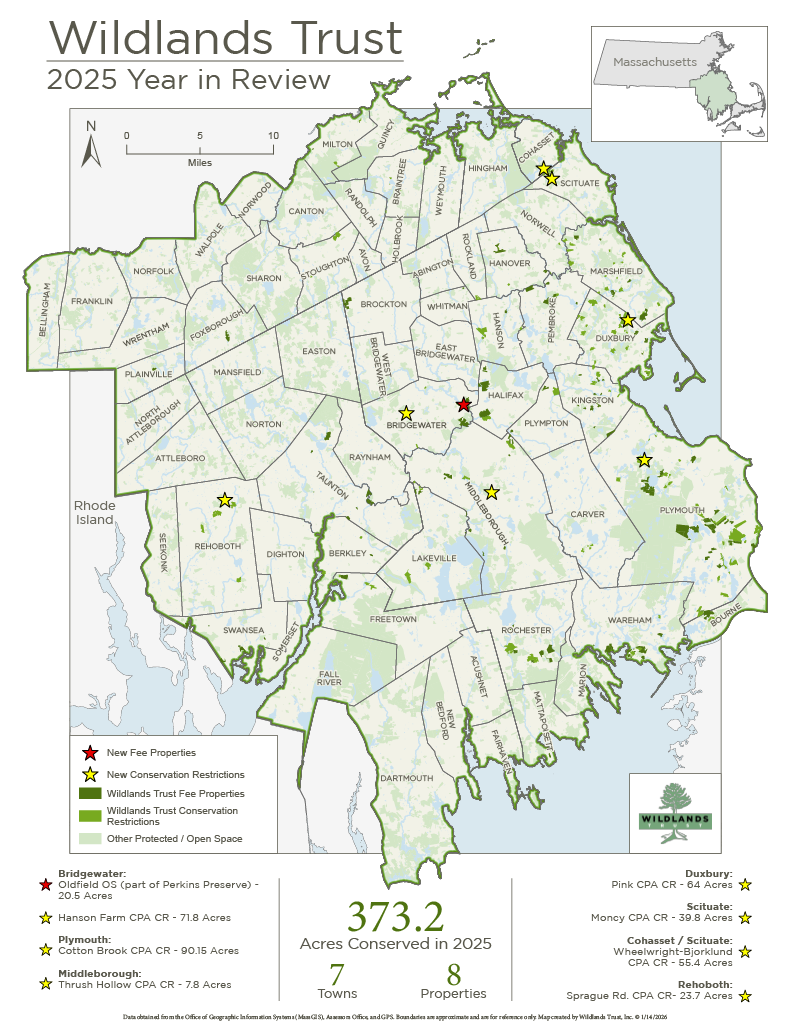

What’s New at Wildlands

Year in Review: What We Protected in 2025

Plus: What You Read in 2025 — Top Stories from Wildlands E-News

New Year’s Reflections from the Land Protection Office

By Scott MacFaden, Director of Land Protection

Helping CPA Towns Turn Investment into Impact

We completed five new Community Preservation Act (CPA) Conservation Restrictions (CRs) in 2025: the Hanson Farm CR in Bridgewater, the Cotton Brook Preserve CR in Plymouth, the Thrush Hollow CR in Middleborough, the Pink CR in Duxbury, and the Sprague Road CR in Rehoboth. Although these CRs are in different communities and protect different types of habitats, the connecting thread between them is that they all represent locally driven land conservation projects enabled in large part by CPA funds. A quarter-century after it became law, the CPA remains an invaluable asset to community-driven land preservation.

Hanson Farm in Bridgewater.

Saving Farmland

The Hanson Farm CPA CR in Bridgewater was the highlight of the year for farmland protection projects. We now co-hold a CR with the Town of Bridgewater on the 72-acre Hanson Farm, the last working farm of scale in Bridgewater and regionally beloved for its ice cream stand and farm store. The CR will forever ensure the protection of this last bastion of Bridgewater’s agricultural heritage.

Conserving Land in New Towns

We continued to expand our geographic footprint by adding two new communities to our portfolio through the acceptance of two CPA CRs previously held by the Maxwell Conservation Trust in Scituate and Cohasset. Collectively protecting 96 acres in the West End neighborhood, primarily in Scituate but including a small portion in Cohasset, these CRs encompass a variety of landscapes and habitat features, including scenic woodlands and vernal pools.

Founded in 1997, the all-volunteer and locally based Maxwell Conservation Trust prioritized protecting land in the West End neighborhood and worked closely with the Town of Scituate to successfully complete multiple projects in that area, including the two properties protected by these CRs. Similar to several all-volunteer land trusts Wildlands has worked with, the Maxwell Conservation Trust eventually determined it could no longer continue as an active organization and sought a qualified successor to accept an assignment of its CRs before shutting down its operations. Learn more here.

Looking Ahead to 2026

We’re excited about several new farmland projects that are either underway or in the early stages of preparation. In the former category, we’re working with the Friends of Holly Hill Farm and the Town of Cohasset toward completing a CR on a currently unprotected portion of that farm. If all goes as anticipated, the CR will be completed by early summer. In the latter category, a project that would achieve a permanent preservation outcome for Hornstra Farms in Whitman is in the planning stages.

Best of E-News: What Inspired You in 2025

When people are informed, connected, and inspired to protect the nature around them, the entire region benefits. That is what Wildlands E-News is all about. Below are five of the most-read E-News articles from 2025.

Curious about a particular aspect of our work or our region’s natural resources? Tell us in the comments below, and we might explore your question in a future newsletter!

Taunton River at Wyman North Fork Conservation Area in Bridgewater.

1. Human History of Wildlands: The Taunton River Watershed

Key Volunteer Skip Stuck continued his popular series in 2025, spotlighting the human history hidden beneath the foliage of Wildlands’ most beloved preserves. In this most-viewed article of 2025, Skip broadens his focus to an entire region—the Taunton River watershed, where Wildlands has prioritized land protection for decades due to its unique ecological and cultural heritage.

2. Land Protection Update: Duxbury, Scituate, Cohasset

Scott MacFaden recounted Wildlands’ recent land protection victories, including a Conservation Restriction (CR) next to O’Neil Farm in Duxbury and two CRs in Scituate and Cohasset, Wildlands’ first-ever acquisitions in those towns.

Wildlands members receive exclusive updates from our land protection office through their complimentary subscription to our biannual print newsletter, Wildlands News. Become a member today at wildlandstrust.org/membership.

3. White Pine: A Common Tree’s Uncommon History

In his Wildlands E-News debut, local farmer, naturalist, and volunteer hike leader Justin Cifello shines a light on a somehow overlooked giant of our forests—the white pine. From their symbolism in Indigenous and colonial cultures to the surprising reason behind their occasional deformity, Justin traces a history that places the white pine at the center of our region’s social and ecological identity.

4. Welcoming New Staff

We said hello to four new staff members in 2025. Rebecca Cushing joined us in January as one of two new Land Stewards. Callahan Coughlin joined us in February as the second. Already, Rebecca and Callahan have earned new titles to reflect their increasing responsibility: Rebecca is now our Stewardship & Volunteer Coordinator, while Callahan is our Stewardship & Training Coordinator.

In May, we welcomed Rob Kluin as our new Donor Relations Manager. Rob succeeds Sue Chamberlain, who retired after 12 years at Wildlands. In August, Jason Risberg came aboard as our first-ever GIS Manager, giving a major boost to our mapping and analysis capabilities.

Town of Avon Select Board Member Shannon Coffey cuts the ceremonial ribbon to open Fieldstone Preserve.

5. Fieldstone Preserve Gives Avon & Brockton Residents New Place to Enjoy Nature

In November, Fieldstone Preserve opened to the public, providing Avon, Brockton, and surrounding communities with new access to nature in the region’s densest urban landscape. The 30-acre woodland features 0.7 miles of trails that connect to D.W. Field Park. The Town of Avon acquired the property in 2024 with funds from a state grant and a private foundation, secured by Wildlands Trust. The grand opening ceremony brought together public officials and nonprofit leaders working collaboratively to improve the area via the D.W. Field Park Initiative.

Human History of Wildlands: Pudding Hill Reservation

Chandler’s Pond at Pudding Hill Reservation in Marshfield.

By Skip Stuck, Key Volunteer

Pudding Hill Reservation in Marshfield was donated to Wildlands Trust in 1991 by Elizabeth Bradford. Though relatively small at 37 acres, the preserve has a varied terrain, including an upland ridge, frontage on Chandler’s Pond (from which a bubbling brook becomes the South River), and the 128-foot Pudding Hill itself. A mowed 0.4-mile trail provides easy access to the preserve from the parking area on Pudding Hill Lane. Today, Pudding Hill Reservation offers visitors a relaxing sanctuary just minutes from Marshfield Center.

As with many of the properties featured in this “Human History of Wildlands” series, the present-day tranquility of the area belies the long human impact on the land in and around Pudding Hill Reservation. Like Hoyt-Hall Preserve and Phillips Farm Preserve, other Wildlands properties in Marshfield, this land has been in constant use for generations, including Native Americans for thousands of years and European settlers over the last four centuries. With human habitation comes change.

The North and South Rivers have always been heavily utilized by Native people, including the Massachusett Tribe, for hunting, fishing, and shell fishing, and as water highways for transport and trade throughout Southeastern Massachusetts.

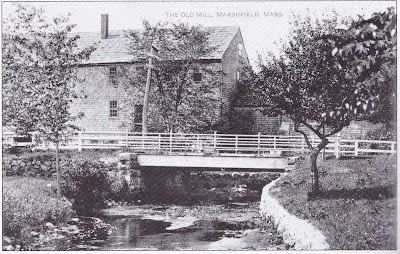

Marshfield’s first gristmill, founded in 1654 by William Ford and Josiah Winslow. Photo circa 1940. The site is now Veterans Memorial Park, directly adjacent to Pudding Hill Reservation. Via North and South Rivers Watershed Association.

After 1620, Pilgrims from the Plymouth Colony were quick to see these benefits. Settlers began to arrive in Marshfield before 1640. As you will remember from other installments of this series, one of the first orders of business in areas with flowing water was the building of mills—especially gristmills. With this goal in mind, Samuel Baker, John Adams, and James Pitney purchased the Pudding Hill property along the South River. By 1659, Samuel Baker's gristmill was up and running, made possible by the damming of the South River to create Chandler’s Pond. Other dams and mills followed in 1706 and 1771.

But bigger things were on the horizon. In 1810, as the Industrial Revolution was beginning, waterpower was once again instrumental in the establishment of the Marshfield Cotton and Woolen Manufacturing Company. A network of support enterprises helped the company thrive through the first half of the 19th century. Leavitt Delano's blacksmith shop and Elijah Ames' carpentry shop, among others, produced barrels, tools, and other necessities. Other factories produced textile dyes. Farming was largely replaced by factory work, which necessitated housing, boarding houses, a store, and a school.

However, the second half of the 19th century was the time of "Manifest Destiny," and throughout New England, the opening of the American West drove a significant emigration of local farmers to the Great Plains and beyond. In addition, larger manufacturing cities such as Brockton, Lowell, and Lawrence drew workers away from the smaller towns. The Cotton and Woolen Company closed in 1860, but later Gilbert West purchased the water rights to the property and ran a saw and gristmill until the 1920s.

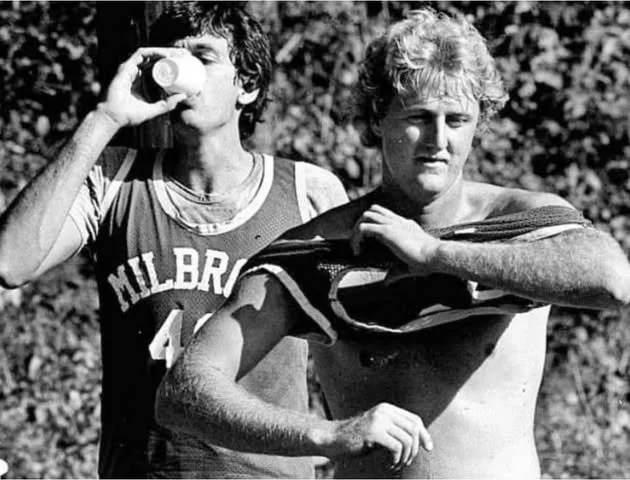

Camp Milbrook campers swimming in Chandler’s Pond in 1967. Via UMass Boston, Joseph P. Healey Library.

Marshfield was gradually becoming the seaside vacation and bedroom community of today. In the 1920s, Pudding Hill and Chandler’s Pond became the summer home of the Bradford family. In the 1950s, the Bradfords moved in full-time. In an interview, Elizabeth Bradford, a direct descendant of Plymouth Colony governor William Bradford, relates the history of Pudding Hill as a quiet, peaceful refuge—not just for her family, but for many others. From about 1938 to 1985, Pudding Hill was the location of Camp Milbrook, a summer camp that served hundreds of children over its lifetime. It also gained local fame as a training camp and teaching clinic for the Boston Celtics, where coach Red Auerbach and stars like Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, and Robert Parish taught basketball fundamentals to summer campers.

After the camp closed, the Bradfords started thinking about what would happen to the property they loved. Housing and other development was erasing much of the historic farmlands and woodlands in town, and Elizabeth Bradford was committed to saving Pudding Hill and preserving its beauty. In 1991, she donated it to Wildlands Trust. Today, it is a popular destination for hikers, bird watchers, and nature lovers who use its trails and open space for all the outdoor activities that Ms. Bradford intended. It will remain as such forever under Wildlands’ stewardship.

Kevin McHale and Larry Bird at Camp Milbrook. Video: Red Auerbach instructs kids at Camp Milbrook in Marshfield in 1974. Source: GBH Archives.

We hope you will take advantage of what Wildlands Trust offers in Marshfield and throughout Southeastern Massachusetts. Please come and visit. To learn more, look over the following resources used in researching this article:

The Power of Water: Milling and Manufacturing in the North River Valley by Kezia Bacon, NSRWA, April 2008.

An excellent piece that delves more deeply into the history and stories of the entire North and South River watershed, including several other areas that Wildlands preserves, such as Hoyt-Hall Preserve, Cushman, Preserve, Willow Brook Farm, Tucker Preserve/Indian Head River Trail, Phillips Farm Preserve, and Cow Tent Hill Preserve. I thank Ms. Bacon for writing it and hope you will enjoy reading it.

Marshfield: A Town of Villages 1640 - 1990, by Cynthia Hagar Krussel and Betty Magoun Bates, Historical Research Asociates,1990.

Interview of Elizabeth Bradford, by Kezia Baker, WaterWatch (the newsletter of the North and South Rivers Watershed Association), Sep. 1993.

North and South Rivers Watershed Association website: www.nsrwa.org.

Pudding Hill Reservation, Wildlands Trust: wildlandstrust.org/pudding-hill-reservation.

As always, a special thanks to Thomas Patti for editing this piece.

Doing vs. Being: Q&A with Yoga & Dance Teacher Grace Junek

Grace Junek.

By Thomas Patti, Communications Coordinator

Grace Junek is a yoga and dance teacher with 15 years of experience. Through group, one-on-one, and online programs, Grace aspires “to help make the world a better place by inspiring joy, supporting healing, and empowering self-awareness.” Learn more about Grace and her business, Be Inspired with Grace, at beinspiredwithgrace.com.

Grace led popular yoga classes at Wildlands Trust before the COVID-19 pandemic brought our programs to a halt in 2020. Now, she is back, offering two programs in our Community Conservation Barn at Davis-Douglas Farm: Yoga for WellBeing every Wednesday in February and March and Sole to Soul Movement across three Sundays in April. Learn more and register for Grace’s upcoming programs here.

Earlier this month, I spoke with Grace about her inspiration behind these programs, the benefits of yoga and dance, and the connection between mindful movement and nature.

TP: You have two programs coming up at Wildlands, Yoga for WellBeing and Sole to Soul Movement. Can you tell me a bit about those?

GJ: For Yoga for WellBeing, I wanted to create a class that feels comprehensive—one that addresses the body, mind, and spirit. The mind piece might begin with a short reflection. The physical aspect focuses on keeping the body strong, flexible, and balanced. And spiritually, it can be as simple as connecting with the breath and allowing that to become a doorway to connecting more deeply with yourself.

Sole to Soul Movement is really an extension of what I’ve been doing for the past 15 years. I’ve been teaching Latin dance, which is a high-energy style that draws from many genres within the Latin music world. It’s super fun. At the same time, there has always been a therapeutic element to the work. Somatic movement is incredibly beneficial for the body in so many ways. Sole to Soul is a pilot class focused on turning emotion into motion—processing feelings without words or thoughts. I’m really excited about it.

Who is the ideal audience for these programs?

Anyone who is truly serious about self-care. I’ve been doing this work for a long time and have taught everyone from teens to people in their 80s. While most participants have been female, there have also been many males over the years. Ultimately, it’s about self-care.

One of my favorite quotes is, “Self-care is about giving the world the best of you instead of what’s left of you.” That really captures what I’m trying to offer through this work.

What are the benefits of yoga and dance?

I consider both yoga and dance to be meditative practices. When you’re practicing them, they naturally bring you into the present moment. There’s no tomorrow, no timeline, no yesterday—just right now. They help you connect with yourself in the moment.

There’s an important balance between doing and being. So much of life is constant, relentless doing, and these practices invite presence and awareness. My hope is always that the mindfulness cultivated in class extends into other areas of your life. And it does.

Sunrise Yoga with Grace Junek.

Why are you partnering with Wildlands? How does your work connect to nature?

Nature is truly the cornerstone of human wellbeing. I deeply admire the work that Wildlands Trust does. Being able to get out into nature allows us to reset, disconnect, and gain perspective—to remember that we are part of something much bigger than ourselves. That awareness plays a central role in wellbeing.

There is also a powerful synergy between nature and meditative practices. It’s not just about understanding that connection intellectually, but feeling it and living it through experience.

There’s also a healing aspect to nature. When I use the word “healing,” I’m not just referring to recovery from illness. I’m also talking about healing from the stresses of everyday life. That’s the kind of healing nature so beautifully supports.

Who are you? How did you arrive at this work?

My heritage is Brazilian Portuguese, so music and dance have been part of my life since I was born. I came to yoga in my 30s. For me, dance saved my life, and yoga healed it.

I was a clothing designer for more than 25 years while raising three children. In my 40s, I reached a point where that career became too demanding, and I made the decision to walk away. I naturally returned to dance and yoga—not professionally at first, but for my own healing, balance, and well-being. From there, I realized I could take two of my greatest passions and turn them into my life’s work. When I saw how deeply these practices impacted others, the work began to expand organically.

This is not a hobby—it’s my life’s work. I truly believe this is how I can help make the world a better place. When individuals become healthier from the inside out, that wellbeing naturally ripples outward to others.

What can people expect from you when they attend their first class?

Over the years, the feedback I receive most often is that my work is inspirational.

There are three core values at the heart of everything I do. The first is quality. When people come to my classes, there is a level of quality that is never compromised. I deeply respect that people are carving time out of their busy lives, and I want them to leave feeling glad that they came.

The second is compassion. I’ve always believed that yoga and dance meet you exactly where you are. There is no competition—not even with yourself. I emphasize acceptance and non-judgment, whether you’re a seasoned practitioner or a complete beginner. In my dance classes, I always say there’s no such thing as a mistake—only unexpected solos. If you’re having fun, you’re doing it right.

The third core value is service. That’s what I’m here to do—to serve others as fully and authentically as I can.

White Pine: A Common Tree's Uncommon History

White pine monoculture at Myles Standish State Forest. Photo by Justin Cifello.

By Justin Cifello

Justin is a farmer and naturalist at Bay End Farm in Bourne and a volunteer for Wildlands Trust. Learn more about Justin (and all our Volunteer Hike Leaders) here.

Familiarity can breed contempt, or at least boredom. Being one of our most ubiquitous trees, the white pine could be overlooked as an object of study. With their uniform growth habit, lack of flowers, and sheer numbers, they may fade into the background in favor of showier plants. However, nothing in nature or history exists in isolation. Even the most seemingly mundane organism has its own story to tell.

Identification and Physiology

White pines are easily identified by their straight trunks and long needles. Their scientific name, Pinus strobus, is a reference to their spirally arranged pinecones, but it offers a useful mnemonic based on another trait: their radially symmetrical branches resemble strobe-light beams, unlike the chaotic branching pattern of pitch pines. Other local conifers, such as yews, spruces, and hemlocks, have much shorter needles, growing directly off of the branches. Cedars, including junipers, have more complex, forking needles, comprised of tiny scales. Only the pines have long needles, which tend to grow at branch tips in bundles called fascicles. Luckily, most of our pine species have a different number of needles per cluster: Jack pines and red pines have two needles in each bundle, pitch pines have three, and white pines have five.

While many of the white pines we see are little willowy saplings, this is the tallest tree species in the Northeast. On the East Coast, it is only rivaled by tulip trees. The largest known in Massachusetts, at about 176 feet tall, is the Jake Swamp Tree, named for the Mohawk chief and founder of the Tree of Peace Society. Its exact location is kept secret to protect it from vandals, but other giants can be seen in the northwest corner of the state, particularly at the Peace Grove in Mohawk Trail State Forest. [1]

Symbolism and History

Haundenosaunee flag. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

An Onandaga story tells of a time of war between five neighboring peoples. A figure known as the Peacemaker came and instructed a man named Hiawatha in diplomacy. In front of the warring leaders, Hiawatha broke a single arrow. He then bundled five arrows together, which no one could bend. Convinced by the demonstrated strength of unity, the leaders formed the powerful alliance known as the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (commonly known as the Iroquois, now an antiquated term). They buried their weapons under a white pine, which, with its five-needled fascicles, became a symbol of peace for the five founding nations. [2]

Flag of New England. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The flag of New England highlights the pine tree’s significance to colonial identity, as well. By the time of colonization, Western Europe had largely depleted its forests, but their enormous ships required enormous trees. Ramrod-straight pines, light and strong, were perfect for ships’ masts. Trees with a 24” diameter were reserved for the royal navy, protected by a policy known as the King’s Broad Arrow. Qualified trees would have an arrow carved into them with an ax. Of course, colonists wanted the timber, too, and the crown was far away. At the historic Harlow House in Plymouth, one can see very wide floorboards—on the second floor only, to keep them from the prying eyes of royal tax assessors. The prohibition was eventually expanded to trees with only a 12” diameter, leading to a violent skirmish in 1772 dubbed the Pine Tree Riot. This early act of defiance is said to have inspired the Boston Tea Party. [3]

Fire and Shade

White pines were abundant and massive trees in the mature forests of pre-colonial Massachusetts, but they were probably not nearly as numerous as they are now. Their population boom owes largely to the decline of their primary limiting factor—fire. As saplings, white pines' thin bark exposes them to fire damage, especially when compared to pitch pines. Unlike beeches, hollies, and other trees with thin bark, white pines do not readily grow new branches or trunks from their stumps, leaving them less likely to recover when burned. Thus, regular, natural fires once gave other tree species a chance to outcompete white pines for sunlight and space on the forest floor.

Since colonial times, however, fire has been stamped out from much of the regional landscape, allowing white pines to proliferate unchecked. In the 1800s, economic changes drove the decline of local agriculture, leaving behind large, sunny tracts of pastures and bogs—perfect settings for white pine domination. Long protected from fire, these woods have matured into single-aged pine monocultures rather than mosaics of unique species. Recognizing the importance of forest diversity to wildlife habitat, water quality, climate resilience, and more, forest managers are now intentionally setting fires—called prescribed burns—to restore the conditions that once brought balance to our woodlands. [4]

Wolf Trees and Tuning Forks

“Tuning fork” white pines. Left: Jacobs Pond Preserve, Norwell. Right: Old Field Pond Preserve/Bay End Farm, Bourne. Photos by Justin Cifello.

Most pine stands have now been cut several times since they colonized old fields. Since loggers prefer the straightest trees, abnormal trees were often left unharvested. Without competition, survivors could expand in all directions. Sometimes called wolf trees, these misshapen behemoths are evidence of disturbance in the forest’s history. Some are victims of the pine weevil, which kills the growing tip of young pines. The surviving branches each become their own leader and bend upwards, giving the tree a tuning fork or candelabra appearance. Stunning to behold, these complex shapes also offer different habitat than more orderly pines. [5]

Though they are now overabundant in much of our region, this species is still a crucial member of our forests. It has served as a symbol for peace and freedom, powered the age of sail, and drove economies. Their towering groves are an inspiring reminder of the tenacity of nature, still achieving remarkable heights despite centuries of deforestation and change.

Works Cited

1. Jake Swamp Tree: uvm.edu/femc/attachments/project/1379/The_Exceptional_White_Pines_of_Mohawk_Trail_State_Forest_copy.pdf

2. Hiawatha and the Tree of Peace: meherrinnation.org/culture/the-great-peacemaker-and-hiawatha/

3. King’s Broad Arrow and Pine Tree Riot: newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/new-hampshire-pine-tree-riot-1772/

4. Prescribed Burns: nationalforests.org/blog/what-is-prescribed-fire-and-why-is-it-important-for-forest-health

5. Wolf Trees: americanforests.org/article/wolf-trees-elders-of-the-eastern-forest/

Fieldstone Preserve Gives Avon & Brockton Residents New Place to Enjoy Nature

Grand Opening Gathers Public Officials, Nonprofit Leaders, Residents to Celebrate New & Future Projects at D.W. Field Park

Town of Avon Select Board Member Shannon Coffey cuts the ceremonial ribbon to open Fieldstone Preserve.

For Immediate Release

Contact: Rachel Bruce, 774-343-5121 x101, rbruce@wildlandstrust.org

Avon — A new conservation area is expanding public access to nature in one of Massachusetts’ densest urban landscapes. On November 20, the Fieldstone Preserve grand opening brought together government officials, nonprofit leaders, and nature enthusiasts from Avon, Brockton, and beyond to celebrate a new woodland trail adjacent to D.W. Field Park—and the innovative partnership that made the project possible.

Fieldstone Preserve permanently protects 30 acres of undeveloped land beside D.W. Field Park, a 700-acre natural oasis serving Brockton and Avon’s 115,000 residents. The preserve’s 0.7-mile trail system includes three entrances, two on D.W. Field Parkway and one off South Street in Avon. Parking is available within D.W. Field Park at the lot west of Waldo Lake. A kiosk at the southernmost park-side trailhead features a trail map, safety guidelines, and information about the area’s natural and cultural history.

The Town of Avon purchased the forested parcel in March 2024. Funding came from the Massachusetts Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness (MVP) program and a private foundation via Wildlands Trust. Over 200 donations from residents across Southeastern Massachusetts unlocked the foundation’s contributions in December 2023.

Brockton Mayor Robert Sullivan presents Wildlands Trust with a mayoral citation for its leadership in creating Fieldstone Preserve.

Speakers at the grand opening included City of Brockton Mayor Robert Sullivan, Massachusetts Senator Michael Brady, Town of Avon Select Board Member Shannon Coffey, Brockton City Councilor Shirley Asack, Wildlands Trust President Karen Grey, Old Colony Planning Council Executive Director Mary Waldron, and MVP Coordinator Carolyn Norkiewicz. Plymouth-based poet Tzynya Pinchback also read a poem inspired by D.W. Field Park through the Writing the Land initiative.

“As a lifelong Brocktonian who used to fish here, feed the ducks here, play golf here, and sled here as a kid, this is a great day for the City of Brockton and for the Town of Avon,” said Mayor Sullivan. “All of us have a shared vision for an unbelievable D.W. Field Park. To be able to add to this is just a wonderful endeavor.” Mayor Sullivan presented citations to Wildlands Trust and the Town of Avon for their project leadership.

“We couldn't have done this without the Edwards family,” Selectwoman Coffey said of the property’s sellers. “People who come to walk these trails for years to come will be following in the Edwards’ footsteps of stewardship and love for this community.”

“I'm constantly impressed by the collaboration of Wildlands Trust with Old Colony Planning Council, the Town of Avon, and the Brockton Garden Club,” said City Councilor Asack. “They are constantly here in the park, preserving our beautiful nature for our kids and for our community. I look forward to our continued collaboration with Wildlands Trust and to the amazing projects they have coming in the future.”

Click here to watch the full ceremony, courtesy of Avon Community Access & Media.

Wildlands Trust Chief of Staff Rachel Bruce and President Karen Grey thank project partners at the Fieldstone Preserve grand opening.

At the ceremony, Wildlands Trust Chief of Staff Rachel Bruce announced the award of $1.4 million in total funding for upcoming improvement projects at D.W. Field Park, including $860,000 from the MVP program for a shovel-ready roadway redesign; $425,000 from the state’s Parkland Acquisitions and Renovations for Communities (PARC) Program for the renovation of the Tower Hill parking area; and $100,000 from the EPA’s SNEP Watershed Implementation Grants (SWIG) for a stormwater management site. These projects will advance the mission of the D.W. Field Park Initiative, a collaboration launched by Wildlands Trust in 2022 to revitalize the park for people and planet.

After the remarks, Selectwoman Coffey cut a ceremonial ribbon to officially open Fieldstone Preserve to the public. A public hike of the new trail ensued, guided by Wildlands Trust staff.

“D.W. Field Park already delivers so many benefits to people and wildlife,” said Wildlands Trust President Karen Grey. “We knew that the best way to expand these benefits was simply to expand the park. But in an urban environment, finding new land to protect is a tall order. We are grateful for the generosity of the Edwards family and the collaboration of the D.W. Field Park Initiative, which made this project possible.”

###

Wildlands Trust works throughout Southeastern Massachusetts to permanently protect native habitats, farmland, and lands of high ecologic and scenic value that serve to keep our communities healthy and our residents connected to the natural world. Founded in 1973, Wildlands Trust has protected more than 14,000 acres of vital lands across 59 cities and towns. For more information, visit wildlandstrust.org.

The D.W. Field Park Initiative aims to revitalize D.W. Field Park by improving recreational opportunities, accessibility, environmental health, and climate resiliency in Brockton and Avon’s largest public open space. Wildlands Trust launched the Initiative in 2022. Partners include the City of Brockton, Town of Avon, Old Colony Planning Council, D.W. Field Park Association, Environmental Partners, Manomet Conservation Sciences, Conway School, and Fuller Craft Museum. For more information, visit dwfieldparkinitiative.org.